By: Isaac Thornley

This post is a part of our new report, Greenwashing the Ring of Fire: Indigenous Jurisdiction and Gaps in the EV Battery Supply Chain.

[READ THE FULL REPORT]

[READ THE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY]

In 2023, the federal and Ontario governments pledged historic subsidies to automakers—up to $13.2 billion to Volkswagen, $15 billion to Stellantis—to build EV battery plants in Canada. While the subsidies show a commitment to secure a fully domestic supply chain for EV batteries, there remain significant gaps. These include a lack of mineral refining capacity in Canada, a lack of infrastructure in mineral-rich regions (such as the Ring of Fire), and, in particular, a lack of recognition of the jurisdiction of Indigenous peoples and their capacity to provide or withhold consent.

Ontario defines supply chains as “the integrated systems of organizations, people, activities, information and resources involved in supplying a product or service to a consumer.” What this definition glosses over is the question of political-legal authority and the regulatory context within which resource development is carried out—who decides what happens and on whose terms? In other words: who has jurisdiction?

If we assume the “supply chain” is a system that depends on integration and coordination between jurisdictions, it is clear that a failure to recognize Indigenous jurisdiction over lands is a tremendous source of uncertainty, creating a “broken link” in the fully integrated supply chain that the government of Ontario envisions.,

Indigenous peoples in Canada wield a unique strategic power to disrupt business as usual, due to their specific legal rights, their capacity and willingness to exercise jurisdiction over their territories, and their proximity to key logistical “choke points.” As Pasternak and Dafnos argue, “no other political group in Canada shares with Indigenous peoples the legal and material power to consistently intervene in the flow of capital from coast to coast and over international borders.”

Ontario treats the Ring of Fire as a key for unlocking the raw resources deemed necessary for the emergent EV battery supply chain, but the region is politically fraught, ecologically sensitive, and lacking in terms of infrastructure and community buy-in. The provincial government is assessing three all-season road proposals in the region to facilitate extraction, working with two proponent First Nations (Marten Falls and Webequie), who cite a dire need for community infrastructure and connection. Despite years of systematically neglecting Indigenous communities in the region, failing to provide the basic infrastructure and services necessary to meet their needs—resulting in a 30-year boil water advisory in the nearby Neskantaga First Nation—state authorities are now intent on paving the way for extraction.

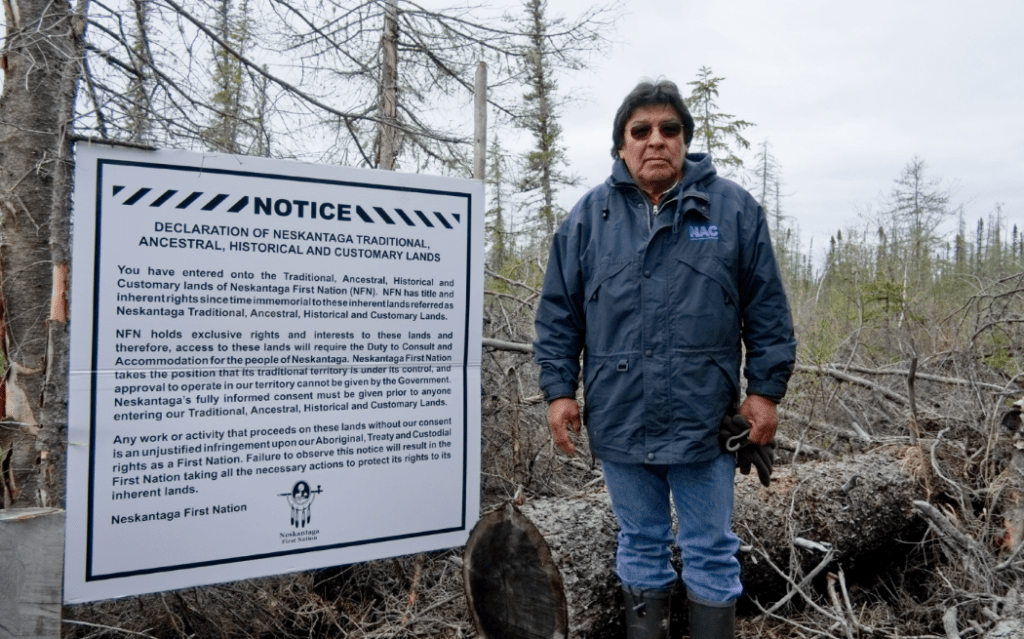

The prospect of development in the Ring of Fire raises long-standing issues of Indigenous jurisdiction, the right of “free, prior and informed consent” (FPIC), and the question of who has decision-making power over specific lands and waters. The Ring of Fire is covered by Treaty No. 9, an agreement signed in 1905-1906 that purports to define the relationship between Indigenous peoples in the area and the Crown. Neskantaga First Nation is one of the many remote First Nations in Treaty No. 9 territory who oppose mining the Ring of Fire. The community’s leadership argues that the notion of strict territorial borders that provide resource certainty for industry and governments is a colonial construction that contradicts their concept of jurisdiction and relations to the land.

Throughout the 2010s, the federal government invested millions in programs aimed at improving “community readiness” for mining activity in the Ring of Fire., From 2013 to 2018, the nine First Nations most proximate to the Ring of Fire claimed their inherent jurisdiction over the region as they engaged in negotiations with Ontario as a united block towards a Regional Framework Agreement. Before this agreement even expired, Ontario began a strategy of bilateral agreement-making with First Nations they deemed “mining-ready,” described by some critics as a “divide and conquer approach.” Since then, two First Nations (Marten Falls and Webequie) have agreed to act as proponents for three road projects, which the company says will make everything go smoother. This political strategy, when combined with Ontario’s free entry mining regime and its narrow interpretation of what the duty to consult and accommodate Indigenous peoples requires, generates uncertainty on the question of how consent can be legally and meaningfully obtained for mining in the Ring of Fire.

In 2023, 10 Treaty No. 9 First Nations launched legal action against the provincial and federal governments, as they attempt to resist future mining activity across their homelands. Attawapiskat, Apitipi Anicinapek, Aroland, Constance Lake, Eabametoong, Fort Albany, Ginoogaming, Kashechewan, Kitchenuhmaykoosib Inninuwug, and Neskantaga are bringing a treaty infringement claim against Ontario and Canada for a failure to recognize that their governing authority in the region was never ceded and remains intact.

The 10 First Nations argue that they hold jurisdiction over the lands and resources in Treaty No. 9 territory; that Treaty No. 9 “did not include the ceding, releasing, surrendering or yielding up of Jurisdiction” but rather results in co-jurisdiction with Canada and Ontario; and that Canada and Ontario have breached Treaty No. 9 by issuing permits and authorizing activities without the consent of the First Nations. The First Nations are seeking $95 billion in damages and demanding that no further resource development be undertaken on their territories without their free, prior, and informed consent.

The failure of the Crown to recognize Indigenous jurisdiction is the biggest gap in the emergent EV dream. The vision of an integrated domestic supply chain cannot be realized simply through subsidizing industry and speeding up mining permits. It will require substantively distributing the benefits of industrial activity to directly affected communities and establishing meaningful consent processes. These processes must provide communities with the power to say “no” to development that they deem to be against their best interest and/or counter to their own legal obligations to protect lands and waters. As it currently stands, multiple Treaty No. 9 First Nations have made themselves clear: “no Ring of Fire mining without consent.”