By: Anne Spice, [Toronto Metropolitan University, Canada]

This post is a part of our Keywords for Decolonizing Geography series. It was originally published as part of an article titled “Infrastructure, Jurisdiction, Extractivism: Keywords for decolonizing geographies” in the journal Political Geography.

I started looking to the terminology of infrastructure, first, to describe colonial invasions, after interviewing Freda Huson about the Indigenous land occupation she has built on Unist’ot’en territory (Spice, 2019). Freda appropriates the term “infrastructure” to describe our critical infrastructures, as those belonging to Indigenous people. Her use of the term is a response to the weaponization of language that came in the form of legislation put forward to designate any threats to critical infrastructure as terrorist activity (Bill C-51, the Anti-Terrorism Act, 2015). The reclamation and appropriation of the terminology of “infrastructure” challenges the state’s weaponization of that language. It is a reclamation and transformation of Canadian legal language that reifies and legitimizes forms of material invasion, among them colonial materializations like pipelines that are being built through unceded Indigenous territories.

While writing an article about invasive infrastructures, I noticed infrastructure begin to trend as a concept in anthropology (Spice, 2018). For me, this called to mind a sort of bland architecture of description, and I wondered if this anthropological treatment might mean turning away from the political and social toward the material, as so much of the “new materialism” scholarship has tended to do. This both intrigued and worried me at a time when I saw the construction of new infrastructures—pipelines especially—threatening Indigenous territories, autonomy and access to ancestral lands, and ways of life. But I think that what Deborah Cowen (in this intervention) is pointing to is that infrastructure is really about motion and movement. Infrastructures are not static or frozen in time. We can use the language of infrastructure to describe the material forms that some of these deeply political motions or movements take, and we can also look for the ideology that sticks to infrastructures through their conception, construction, and use.

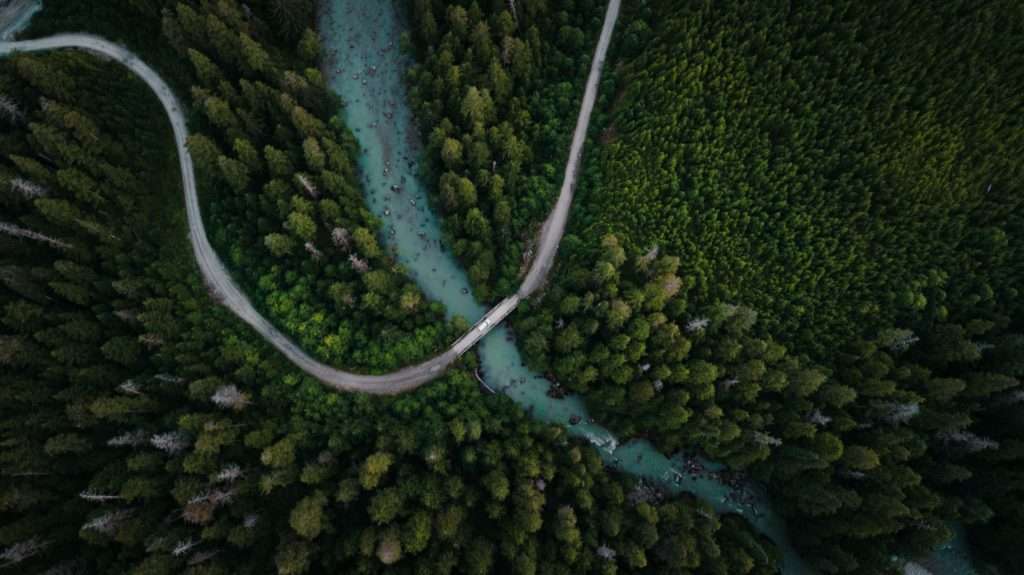

The second reason the concept of infrastructure is critical to the Indigenous terrain of struggle is because infrastructures require maintenance. It is relatively straightforward to think about maintenance in terms of colonial modern infrastructure. We easily think of highways, pipelines, and other things that require maintenance to avoid going into disrepair. But it’s important to apply that to Indigenous infrastructures and alternative infrastructure, as well, for these are infrastructures that also require maintenance. This is a maintenance that is embedded in the relationships that Indigenous people have with our lands and all the beings that inhabit those lands. If we think of a river as infrastructure, then it’s not something that is built and then walked away from, nor something that just exists in space as material. It may have that capacity, but it’s also something that requires constant maintenance and care. It’s something within which we are also embedded – a web of relations – maintaining and holding up Indigenous and natural law, making sure that our rivers stay healthy. If our attention is drawn to those healthy relations, then we are going to treat these infrastructures differently.

Another reason why I think infrastructure is an important terrain of struggle is that infrastructures are made material in that they are literal matter in place. They are constructed and become part of the built environment through the work of putting things in motion. They transport people and matter, which are then used to build, settle, or sustain particular forms of living. Infrastructures play a critical role as material in motion in several senses. The first is literal, as modes of transport. But they also work in the service of a future imaginary. When we think about pipelines as critical infrastructure, those pipelines are in service of the future that is still dependent on fossil fuels. Pipelines materialize that future and its violent effects—Indigenous dispossession and displacement, environmental destruction and contamination, wealth disparity, imperialist war, and climate change.

Infrastructure, in this sense, depends on a set of global economic relations that have roots in racial capitalism. Anthropologists have written about the way that state infrastructure projects, in particular, are grounded in this imaginary of modernity (Coronil, 1997; Limbert, 2010; Mrazek, 2002). So, what are these infrastructures going to make possible for settler states? The imaginary element of infrastructure is important because we can push back against that vision, based in colonization, when we’re thinking about what world they are bringing into being and whether we want to participate in those kinds of worlds.

Alternatively, when we’re looking at maintaining good relations with our lands and at the ways that infrastructures–our infrastructures–are a part of those relations, we can also imagine a different future. We can be creative about the ways that we make those connections. We need to see the material connections between the health of our rivers, the future that we want to inhabit, and the future in which we want future generations to be able to live. Infrastructure can make material the connections between actions in the present and the possible, built worlds of the future. That’s why I think it continues to be a helpful concept, and how it links into critiques of colonialism.