Infrastructure Beyond Extractivism: Material Approaches to Restoring Indigenous Jurisdiction

The Project

Our Project

Assembling Infrastructures of Indigenous Jurisdiction

Our project proposes to enact experiments in transformative infrastructure with the aim of restoring Indigenous jurisdiction. The ground-breaking 2019 Yellowhead Institute Red Paper documents how Indigenous-led consent processes based on fulfilling responsibilities are already having the effect of restoring Indigenous jurisdiction and reclaiming Indigenous lands and waterways, foodways and lifeways. We propose to systematically document and evaluate this ongoing work to determine which strategies and approaches have the most success.

Across three clusters of projects, we ask:

- What is the relationship between infrastructure and jurisdiction?

- How can remaking the material systems that sustain collective life enact Indigenous jurisdiction?

- How can the “just transition” to sustainable economies be imagined and infrastructured to foreground Indigenous knowledges and governance systems?

What is "Jurisdiction Back"?

Our project offers an agenda for fundamentally re-making our socio-technical systems; for conceptualizing and building infrastructure otherwise. If infrastructures of extraction constitute the ‘spine’ of the settler colonial nation (LaDuke and Cowen 2020), we propose a vital new central nervous system: communities energized by a completely different conception of what ‘critical infrastructure’ entails. Infrastructure otherwise is the “essential architecture of transition to a decolonized future” (246). Instead of rebuilding infrastructure to serve an economy and settler colonial mentality that enhances the means of life for some by withdrawing them from others, we will offer conceptual visions that foster renewed relations for prosperous, caring and just collective futures.

Historically and continuing to today, it is through claims to jurisdiction, and the materialization of those claims through infrastructure, that governments have sought to replace the legal and political authority of Indigenous peoples with their own. We see ‘Jurisdiction Back’ as offering a profound transformation in legal, economic, and material relations and practice towards honouring Indigenous rights and authority, and in doing so, cultivating a more just and sustainable future for all those who live and work on this land.

Past Events & Workshops

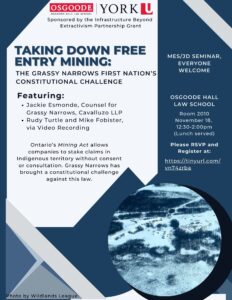

“Taking Down Free Entry Mining: The Grassy Narrows First Nation’s Constitutional Challenge”

Featuring: Jackie Esmonde, Rudy Turtle, and Mike Fobister

November 18, 2024

Sophia Jaworski, “The Mining Industry is a Chemical Industry”

September 19, 2024

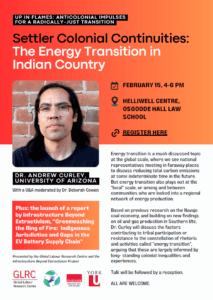

Andrew Curley, “Settler Colonial Continuities: The Energy Transition in Indian Country”

February 15, 2024

Past Workshops

June 2022

“Infrastructure Imaginaries: Re-making and Enacting Indigenous Jurisdiction.”

Presenters: Winona LaDuke, Jason Lewis and Michelle Daigle

April 2022

“Engineering Indigenous Jurisdiction.”

Presenters: Karletta Chief and Maya Trotz

December 2021

Pilot Project Presentations: “Building a Climate and Cultural Centre at Lax an Zok, Supporting the Meziadin Indigenous Protected Area” and “Governing Lifelines: Ice Roads and Indigenous Jurisdiction.”

Presenters: Tara Marsden and Shiri Pasternak

October 2021

Community-Based Research Presentations on two pilot projects: “Evaluating the use of an experimental greenhouse and root cellar to restore jurisdiction” and “Expanding Anishinaabeg Sugar Bush Jurisdiction.”

Presenters: Kanahus Manuel and Christine Sy

September 2021

Keywords Session on “Infrastructure,” “Jurisdiction,” and “Extractivism,” followed by a Q & A.

Presenters: Anne Spice, Deb Cowen, and Dayna Nadine Scott.

Conceptual Approach

In recent years, proposals for new infrastructures have become flashpoints of violence, tension, and competing claims of jurisdiction; we need only look to the massive contestations over oil and gas pipelines, hydro power, and mining roads. Infrastructure has long been and continues to be a means of dispossession, a “material force that implants colonial economies and socialities” (Cowen 2017). The colonial settlement of this continent was engineered through the laying of transcontinental railroads (Estes 2019, Karuka 2019) and massive hydroelectric power systems (Fleming 2017). Yet, Indigenous communities continue to endure major infrastructure deficits in areas of basic services such as drinking water and wastewater systems.

Re-Thinking "Critical Infrastructures"

Anne Spice’s re-theorization of ‘critical infrastructures’ is crucial. Spice argues that we need to move away from framing critical infrastructures as the networks that maintain the efficient operation of government and industry, to a conception that centres the interconnected networks of human and other- than-human beings that sustain life. As Spice (2018) says, “These are relations that require caretaking, which Indigenous peoples are accountable to” (42). Spice forces us to confront the question of what counts as ‘vital’ and for whom? Similarly, LaDuke and Cowen have argued (2020) that “infrastructure is not inherently colonial – it is also essential for transformation; a pipe can carry fresh water as well as toxic sludge” (245). Drawing this distinction between the kinds of “invasive infrastructures” (Spice, 2018) that governments today often accept as ‘critical’ and the kinds of life-giving and sustaining infrastructures that Indigenous communities need and seek to protect, we propose to address the systemic infrastructure challenges that continue to plague Indigenous communities in Canada, applying and testing innovative approaches to exercising jurisdiction.